In praise of hedonism

Why I will not make any new year's resolutions

Economics has occasionally been likened to providing rationalisations for someone smashing their balls with a hammer. Often, the principle of preference maximisation has been stretched to its logical, and socially unconventional (absurd?) conclusion. A caricature of economists is that we are incapable of comprehending how the median human functions, with their pathologies, and consider them as homo economicus robots, devoid of emotion and with perfect vision of how the world operates. Yet as I will demonstrate, pathologies can be themselves consistent with rationality. Does this mean we overrate being rational, and that we should prioritise some notion of virtue ethics? This post will answer this question decisively in favour of rationality. If we are rational, as this post will argue we are, then we will be happiest via simply doing what we want. For this reason, I will not make any new year's resolutions.

Initially when writing this, I conceptualised this blog as a personal avocation in practicing theory. Later on however, this turned into a philosophy exercise, with a particular focus on ethics. Hence, perhaps this post will attract two groups of readers: those interested in economics and those interested in philosophy. For the latter, those without an economics background can skip the model and sections IV-VI (except the italics). For the former, I will be returning to the model in a subsequent post. Regular readers will know my strong utilitarian and consequentialist stance on ethics. I hope to persuade others that, if we consider individuals as capable of making rational choices (which most subscribing to deontological or virtue ethics do, or else they would disregard their emphasis on personal responsibility), then you should accept preference utilitarianism as the best moral framework.

I. Distinguishing rationality from disease

A more typical example than smashing your own balls is that us economists conceptualise addictions not as diseases (unlike the medical consensus), or moral defects, but rather as individual choices like any other. Most of this post will be a special tribute to this (stereotypically Beckerite) model of addiction: a seasonal tribute given that most will make new years resolutions that, if actually enacted, would make you miserable; explaining why they are rarely credible commitments.

The disease model, popularised by twelve-step communities and predominant in the recovery communities, posits that addicts suffer from an allergy to their substance or activity of choice - as soon as they consume that good, they endogenously spiral out of control until they receive divine treatment (conveniently only by AA and related groups, and their canonical text The Big Book). In this process, they lack the agency to cease committing acquisitive crimes to finance their habits, or prioritise their relationships, hold down their jobs, or maintain their commitments to bills.

Yet, as Bryan Caplan is fond of arguing, most drug users cease using without any assistance. Most famously, almost all veterans of Vietnam stopped using heroin cold turkey when returning home. When Mao threatened the death penalty in lieu of forced treatment for addicts, addiction in China plummeted. Perhaps there is indeed a dopamine hijack, yet this considers the utility of only one good in our utility function, not the tradeoffs nor our constraints. Perhaps, as AA types will argue, they were “never true addicts/alcoholics” in the first place, yet this is the classic “No True Scotsman” fallacy. From selection effects, of course the recovery community is composed of the most dysfunctional, yet their success rates are low. If addiction was a disease and AA was an effective cure, then we would expect success rates analogous to those of FDA approved medications.

Moreover, there are many “functional addicts” out there [1]; is their use a disease or more analogous to an unhealthy vice like smoking or overeating, with less immediately destructive effects? How can we distinguish, upon first use, an addict with a disease vs a healthy individual? We only know the answer ex-post, and there is an obvious chicken and egg issue. What about the former dependent alcoholics (with shakes), that in fact can learn to eventually take one drink? In fact, what separates an addict or alcoholic with a disease from harmful consumption in the first place? These facts are simply inconsistent with a disease model. Of course, the disease model, via absolving addicts of responsibility, is socially desirable in large quarters, and assists in enabling an addict by helping them to justify their maladaptive choices. Yet epistemologically, it is a bad model, exerting substantial yet hidden economic costs via its influence in anti-discrimination laws. Addiction is a strange disease when, unlike when you are diagnosed with cancer or dementia, it is indeed highly sensitive to budget constraints and opportunity costs…

Consider rationality as:

Holding preferences over a set of goods or services (completeness).

Those preferences are logically consistent (transitive), so if a>b, and b>c, then a>c must hold.

A rational agent will sacrifice x amount of good a to consume good b (continuity).

Behaving according to those preferences (revealed preference), given the information they hold. So if someone consistently chooses good a over b, they yield the preference a>b.

Addiction is perfectly consistent with this. I would argue, in fact, that addicts meet the criteria for this definition of rationality more than most (their preferences are highly consistent and transitive: they sacrifice almost all else for that substance!). The colloquial definition of rationality is making the best (most logical) decision using the information and evidence you have. This formalises that approach to everyday decision making. In the jargon, our preferences can be modelled as a convex and continuous function in R^n, homogenous of degree one. Indifference curves are contours of this in R², hence why they never cross. This is unlike mental illnesses like schizophrenia: characterised by erratic, intransitive behaviour.

II. An addictive model

Here, I will present the Becker and Murphy model of addiction as I understand it, with some differences in notation. Our agent yields a preference over two goods, a and b. Good a is the drug of choice [3], and b is everything else. Moreover, good a is characterised by some form of increasing marginal returns to its consumption, which is our key departure from convention. In other words, the more you engage in your addiction, the more you want that drug [3].

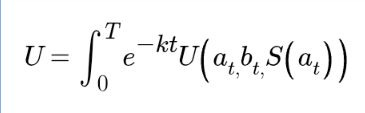

Our utility function is given by:

Ut = U(at, bt, S(at))

for (S(at) - S(at-1))/S(at-1) = at - δS(at-1) - D(at-1).

Intuitively, consider S(.) as representing the notion that addiction is an investment, into a new hobby. Hence, S(.) reflects your investment into the activity, described as a learning process tantamount to Romer’s learning by doing model. As I will describe later, its dynamics are even analogous to that of capital, complete with a steady state. S(.) itself is concave in a, so is subject to diminishing marginal returns, yet its inclusion into our utility function generates increasing marginal returns to the utility of a overall. Present utility is dependent upon our past consumption of a, and future utility changes in accordance with our addictive consumption habits. Let δ be any real constant that encapsulates cravings or tolerance effects from our past consumption. Then the more we crave the substance, the more we must consume a to maintain the same utility over time. D(.) represents our past expenditures (in terms of all resources allocated, not just money or time) on the habit, and is not a sunk cost as it endogenously affects craving or tolerance. Hence, we can disaggregate cravings as arising from past consumption per se (the exogenous effect of the drug) and how much we consumed in the past (the endogenous effect given by D(.)); the intensive margin.

Lifetime utility is the sum of utilities over an individual's life T (I forgot to end the integral with dt - surprisingly I make these sorts of notational mistakes often, yet it’s too cumbersome to correct so I'll just acknowledge here):

where 0<=k<=1 is our discount rate. A higher k means that we place less weight on periods further into the future than periods closer to the present. Typically, we would assume that this is equivalent to the risk-free real interest rate, as a dollar today can be invested for (1+r) dollars at t+1. Yet rates of return are heterogenous, so an agent choosing a higher discount rate is perfectly consistent with rationality, and is not necessarily a cognitive bias. Moreover, if we incorporate some measure of existential risk into our discount rate, and we believe there is some nonzero probability that the world will end in our lifetimes, then steeper discounting also makes sense [4].

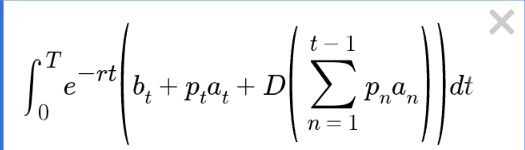

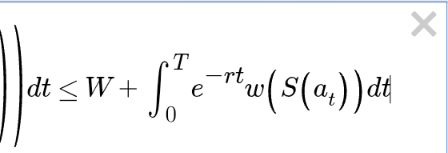

Our agent faces the following constraint:

Here, r is the agent’s chosen rate of return. The price of good b is our numeraire. The functional form of our utility function reflects the path dependency of our utility from consuming a. Exogenous craving or tolerance establishes S(.) as a difference equation, yet that scaling is dependent on endogenous choices from D(.), so we ignore that. W is our initial endowment of wealth, whilst ω(S(.)) is our sum of lifetime earnings. It is endogenous to S(.) as this reflects the loss of income or wealth arising from our addiction over time.

Implicit is the assumption that addiction is costly in the long-run. Addiction is a tax on our human capital via its opportunity costs and the health impacts, hence our marginal productivity of labour, which determines our wage. In general, I take this model to be a profound representation of any harmful behaviours that humans engage in, not just addictions. Obesity, procrastinating with video games? I also think that addiction as a tax on labour market income explains (in part) why addicts yield a tendency to eventually drop out of the labour market. So addiction is only rational if we apply sufficiently high discount rates to future periods. Addiction is correlated with many other pathologies arising from impulsivity, so this prediction holds up well.

See the paper for derivation of the FOCs, yet it seems obvious that consumption of a changes negatively according to changes in its relative price (I will cover the dynamics of S(.) and its constituent variables later). An agent will consume more units of a if k - r is greater: reflecting the fact that individuals may yield a higher risk tolerance or preference for engaging in their addiction relative to investing in the capital market.

The key takeaway is that an addict cares more about their substance than their future incomes or wealth, so for addicts k - r > 0. Yes, they yield preferences for other goods or services (units of b), yet their myopia and increasing marginal returns to the utility of their addictions means that they value b less than a, especially in the long-run. Otherwise, via investing in their (human) capital and forgoing the addiction for a higher future ω, they can consume more b. Ironically, their future consumption of a could also be higher via this same reasoning, so addiction is characterised by the strong desire to consume the drug immediately.

III. Why does this show that addicts are rational?

These results may also explain why an addict's stated preferences are generally for b over a. Their high discount rates effectively “blind” them to the future costs of a, or they behave as if that is the case. The model assumes rationality, so the agent knows how the model operates and the value all parameters take, yet is insensitive to future costs. I suspect however that in reality, most addicts fail to anticipate that they will incur substantial future costs or cravings upon their first use. Did homeless junkies really anticipate being homeless or ending up in jail?

Alternatively, they may believe that they will get addicted at a nonzero probability, yet take the risk anyhow, then they are locked into their habit via these dymamics driven by strong cravings and discounting. In this sense, we can set the endogenous variables according to their expectations instead, with cravings as unknown ex-ante. Of course, the possibility of enduring overwhelming cravings in itself is an abnormality, yet again this is traded off in a rational decision, otherwise abstinence would be impossible. Initially, a preference for b over a may even be true in revealed preferences, yet eventually due to the increasing marginal returns dynamics of S(.) and the costs to future wealth, the drug takes over. Yet for forecasts to be rational, there cannot be any systemic deviations, or any that do exist must average out to zero. There is clearly a systemic underestimate of the future income costs of initially consuming a. Nonetheless, ex-post when the addict is aware, for them to continue their addiction would indeed be a rational choice, as mistakes do not occur continuously. In any case, we can overcome these complications easily by simply modelling some of the unintended consequences (such as homelessness or jail) as unanticipated relative price changes. Indeed, incarceration as a transitory shock models the lifetime wealth effects of such rather well, albeit this is still a fall in ω(.) as you cannot earn much inside. Aside from this, anecdotally even the homeless, via property crime, clearly earn enough to maintain their expensive habits, so the reduction in ω may not be very significant, relative to their markedly different consumption bundle compared to when they first tried the drug. You could model drastically lower life expectancy as ω(.) = 0 for the early dead periods, which is where I suspect ω(.) plays its most salient role.

Regardless, it is common knowledge that drugs and alcohol are unhealthy, and are correlated with ruined lives and other negative outcomes for oneself, yet people still choose to “succumb to temptation” on the first time, which is literally the definition of discounting the future costs. Still not convinced? I implore you to consider a time when you knowingly consumed a food item you know to be unhealthy. Increasingly, we are seeing twelve-step groups for even food or sex. Am I supposed to believe that my strong desire for that chocolate on the shelf is a disease, however loaded in saturated fats it may be? Or my innate reproductive desire, literally essential to the survival of mankind, is a disease? C’mon!

There is one gaping flaw in considering addiction as rational. We have acknowledged that the drug itself can induce overwhelming cravings in some individuals (via δ), independent of their choices. This is consistent with the neuroscientific consensus, that addiction involves a hijacking of the dopamine circuit of the mid-brain. Indeed, this is why disease theory advocates label addiction as a disease or illness. Furthermore, people do not know the value of δ ex-ante (albeit they do ex-post), so it is fair to say that their forecasts of this would be a systematic underestimate, hence biased. If addiction was a result of cognitive bias, then we have a very costly bias. Would it not make sense to try to minimise that cost? You must consider too that δ also contributes to the increasing marginal utility of the drug, so whilst costs from consumption rise over time, so does the utility of getting high. On balance, again for a sufficiently high discount rate, a high δ is not costly at all. As we will see, unanticipated shifts in δ and k are also possible.

Instead of claiming that agents know the value of all parameters in the model, I will instead claim that agents act as if they know the value of all parameters in the model. Knowing something, and acting as if you know something despite your ignorance, fundamentally yields the same outcomes. The distinction may matter for philosophers, yet practically bears no use in a world where only outcomes are observed. Therefore, this claim is sufficient for rationality.

Some imply that rationality may be impossible for anyone. In response to Ben Moll’s critique of rational expectations, I posit that as long as forecasting errors average out to zero, then this is consistent with rational expectations. Similarly, this holds on the individual level too: if on average your errors are zero, then that is consistent with rationality. If the sign and magnitude of your cognitive biases average to zero, then I see no reason why this also cannot be equivalent to rationality, if we are concerned ultimately with outcomes. In fact, as Bryan Caplan most famously argued in his “rational irrationality” thesis, our cognitive biases are simply heuristic shortcuts that most of the time (at least in our evolutionary past) approximated rational behaviour anyhow, with the reduced computation and processing costs of S2 over S1 thinking (to use Kahneman and Tversky's terminology). This is also one reason why I am not a “rationalist” in the LessWrong sense, as I believe that individuals are rational despite their cognitive biases, although it still does make sense to minimise those if such is costless.

Henceforth, I adopt the premise that all individuals are rational, all of the time, except those that do indeed suffer from a rare mental illness such as schizophrenia [5]. From this, the statement that addiction is rational must necessarily follow. In 2025, this premise seems radical. Indeed, the implications are also radical - not just because it implies that the optimal amount of sympathy we should attribute to addicts is zero [6]. As we will see, this means that most virtue ethics can be tossed aside into the bin, and that hedonism (living life according to the maximisation of your pleasure: equivalent to rational utility-optimisation) is in fact the best philosophy to live your life under.

IV. There is a solution…

…but that is not AA, or a higher power, or even abstinence for many addicts. For many, it is in fact optimal to continue with their addiction. Let us now return to the paper, and observe the dynamics.

Our value function from the model is complicated right? I certainly think so! We can make our lives much easier by making the model more tractable. To do this, let T approach infinity, k=r, and D(.)=0. Moreover, by removing the effects of higher discounting than rates of return can justify, and that of endogenous craving, we also approximate the disease model as much as we can. The math is easiest if we model our budget constraint and utility function as quadratic, so our value function becomes quadratic.

We will let the paper deal with the math (or else I would just be copying without any personal or additional insight) now that I have been transparent in disclosing the key assumptions behind these results. What we are interested in is the dynamics of our variables, and their steady-states. Basically, this section will repeat the exercises we did in our primer on economic growth.

The growth path of S(at) is basically a difference equation. The steady-state is when we are consuming just enough to satisfy our cravings. To simplify the notation, I will just write St, and so on, without the functional brackets:

St = (S0 - S*)e^(λt) + S*

for λ = 1/2[k - (k² + 4B)^(-1/2)]

and B = δ(k+δ) + k + 2δ + αc/αu

From these dynamics, multiple equilibria can arise:

If λ<0 then there is a single stable steady-state that the addict converges to, where a*>0.

If λ>0, then the steady-state is unstable, and either the addict will perpetually increase consumption or will opt for abstinence. If λ>0, then B<0. A key feature of this paper is that for addicts, the marginal cost of addiction αc, the coefficient for quadratic cost (influenced by δ and k) rises less than the marginal utility of addiction αu (influenced by δ) over time as a increases. This inequality in marginal values is known as adjacent complementarity, which holds if (k+2δ)αu > αc. The degree of adjacent complementarity increases as k and δ increase. If adjacent complementarity is sufficiently strong for B<0, then the steady-state is unstable and multiple equilibria is possible. Of course, addicts are more likely to display such levels of adjacent complementarity, so we cannot ignore the unstable steady-state as a special case or extension.

As is increasingly apparent, there is marked heterogeneity in the preferences of addicts, which plays a large role in their outcomes. Type I addicts will perpetually maintain their addictions at stable levels (most likely the '“functional addicts”). Type II addicts will increase their consumption as much as feasible (until they end up dead or in jail), or will abstain. Exogenous shifts in δ and k shift the steady-state for type I addicts, and determine whether type II addicts are using or abstaining. However, those shifts will also change λ, so type I addicts can become type II addicts. Confusing right? I will explain the solution further, without any need for The Big Book!

V. Type I addicts: the stable steady-state

Let λ<0. Also imagine a graph of S, total investments into addiction, and a, in 2D space. S is the x-axis, a the y-axis. This corresponds with Figure 1 in the paper. Also suppose there are two functions, St as defined above, and δS which encapsulates the total magnitude of our cravings.

St grows over time to its steady-state, yet that growth is attenuated, assuming that steady-state consumption exceeds initial consumption. Intuitively, our cravings are relatively minor when we first start engaging in addiction, so all else equal, any consumption is more pleasurable, as we are not just trying to abate cravings. However, this pleasure will generate a craving (increasing marginal returns), which then implies that we need more of a to achieve the same effect. So cravings drive the increase in drug consumption over time, yet the rate of this increase is declining over time. Cravings, as a linear function δS, hence rise faster than our investments. Eventually, the gap between our consumption and our cravings will fall until we reach the steady state, S* = δS, which gives our optimal consumption, a*. Any consumption beyond this point will induce a higher increase in cravings than consumption can possibly increase, leaving our addict unsatisfied. Therefore, an addict will eventually stabilise their consumption to only the quantity of the drug necessary to ward off their cravings. A higher craving effect, δ, will increase the growth rate of St, so corresponds to a higher a*. In other words, the more addictive the drug, the higher its consumption.

VI. Type II addicts and multiple equilibria

If λ>0, and initial consumption exceeds the quantity matching cravings, then substance use will increase permanently. At such values, consumption always grows faster than craving, and the gap between them grows.

However, if initial consumption is lower than cravings, then consumption will actually decline over time until the addict is abstinent. The intuition is that cravings are a cost, an implicit tax on addiction. If cravings exceed consumption, then ceteris paribus this actually reduces utility. You must raise your consumption of a to maintain the same utility. Yet for these parameters and initial values, cravings will always exceed consumption - you increase consumption and cravings also increase faster.

Of course, exogenous shifts in δ and k over time are possible. Periods of stress or negative affect may cause an unanticipated increase in δ and vice-versa. Unanticipated events may raise the probability of an existential shock to the future, or accidents may permanently reduce your future utility (think accidents causing chronic pain leading one to be dependent on opioids), leading a rational agent to discount such periods more heavily. These shifts mean that the consumption levels of a type II addict may suddenly find themselves dwarfing cravings, so that addict opts for abstinence. Formerly functional addicts may also shift to the more dysfunctional type II category.

VII. How adjacent complementarity shapes vice

In general, as the magnitude of adjacent complementarity is higher for larger values of δ, the addictiveness of a drug is positively linked to its adjacent complementarity. From this, we can predict the aggregate consumption patterns of a drug.

“Hard” drugs such as heroin or crack tend to yield two distinct equilibria - total abstinence (the equilibrium aggregating the preferences and consumption patterns of the overwhelming majority), and permanently rising consumption to as high as budget constraints will allow (which I suspect is the most ‘conventional’ notion of addiction). Conditional on the initial use of such drugs being nonzero, the probability of “moderation” is relatively low.

On the other hand, there are plenty of drugs whereby stabilisation of consumption patterns, and “moderation”, is the social norm [7], such as alcohol. Indeed, even many harmful drinkers cease to get drunk every day and develop the shakes: instead consistently getting wasted off the clock on the weekend, or getting into unanticipated trouble as a result of drunkenness. Cocaine (powdered) is an interesting case, whereby the vast majority of individuals are abstinent, and there is a substantial contingent of regular users, yet the median user actually indulges on rare occasions (even accounting for underreporting) only.

In this sense, type I addiction models the psychoactive drug consumption habits of the majority rather well, as well as the consumption patterns holding for the vast majority of drugs. When most of us crack open a cold can on a Friday evening, or enjoy a refreshing glass of wine with a meal, we tend to think we are making a rational choice and not suffering from a “disease”. The same cognitive decision-making process that influences our choice to drink alcohol, is the exact same process that addicts use prior to consuming their drug of choice.

VIII. Virtue ethics conflates stigma with evil

Moreover, the addictiveness of a substance is not necessarily linked to its aggregate societal harms. Alcohol is a major risk factor for cancer and dementia, and sudden alcohol-induced fatalities kill millions each year. An incredibly high proportion of crime can be directly linked to alcohol-induced intoxication. Then of course there is drink-driving. Although total consumption of alcohol is a lot higher, so many argue we should expect higher total harms, the harms of alcohol are mainly driven by the right-tail of drinkers - the vast majority are light to moderate drinkers that incur no issues. However, type I addiction seems to prevail as an equilibrium in this market. Similarly, in markets where type II addiction prevails or is more likely, the social costs can be less than we think.

There is little causal evidence that opiate use actually increases property crime; selection bias, and the fact that users tend to display other antisocial pathologies associated with a high k, seems like a far more plausible explanation. There are overdoses, yet as opiates are downers, we would expect a decrease in violent crime with a rise in opiate use. Indeed, I suspect that part of the reason for the secular fall in crime rates over the last few decades has been the shift towards opiate use for those with a high proclivity towards criminality. Not only does this disproportionately kill off those with ASPD, but it also makes them less violent whilst under the influence. Therefore the aggregate welfare costs or gains of the opioid epidemic are not obvious, especially if you consider that high prices (and rates of property crime) and overdoses (from mixing and synthetics) are downstream of prohibition restricting supply. As for cocaine, the costs (heart attacks, nasal issues, poor finances, etc) tend to overwhelmingly fall on individual users, with little obvious externalities [8], beyond again perhaps selection bias. For certain individuals, cocaine use may even promote wellbeing and productivity: those with ADHD are much more likely to have a cocaine use disorder, and in many cases it is only a disorder (having negative consequences) because cocaine use is policed via social sanctions in the absence of effective legal enforcement over this. As a stimulant, moderate doses should act as a nootropic. If we care about the financial impact, then why do we restrict supply?

It seems to me instead that the level of stigma a drug holds tends to be correlated with its addictiveness (as measured via adjacent complementarity and the resulting equilibria), rather than its social harms. The stigma is a function of social deviance, not evil. Therefore, by labelling addicts as irrational sufferers of a disease, we are in fact making a normative moral judgement, not an empirical and positive one. The notion of addiction as a disease, or even a mental disorder, should be treated with the exact same regard as the past inclusion of homosexuality in the DSM is regarded today. Many people will now consider rationality as overrated in terms of its benefits, yet to argue anything else means that you desire to overpower the desires of other people, thereby making them worse off. Unless this is to counteract the externalities imposed on others, I cannot think of a greater evil than that. In that sense, drug users should incur a lot less shame on the margin, whilst paternalists should incur a much higher social stigma.

IX. Virtue is in fact harmful

I consider most virtue ethics as trying to reduce the discount rates of individuals. Stoicism, all the major world religions, and most self-help advice consistently preach the virtues of temperance and delaying gratification. We must sacrifice our present selves for our future selves. Yet, as we rationally set our discount rates ourselves, if we are unwilling participants of practicing virtue, then we will either make ourselves miserable, or revert back to our old habits. Yes, lower discount rates (a proxy for the conscientiousness trait) are indeed consistently correlated with more positive outcomes on almost every socioeconomic variable you can think of. Nonetheless, it is our choice to reap those rewards or forego them, and anything else is suboptimal. If delaying or abstaining from immediate pleasure in favour of some future goal was individually optimal and credible, then there would be a thriving market in binding contracts, rather than sentimental self-help books.

Of course, virtue ethics also promotes prosocial behaviour amongst individuals, especially if you agree with the philosophers that claim our present and future selves are distinct entities. On this front, I sympathise a lot more with the prevailing morality. However, the design of institutions should incentivise us to behave in a prosocial manner, as opposed to prosociality being reliant on us behaving altruistically via self-sacrifice.

To see why, consider Tyler Cowen’s claim that we should all stop drinking as our drinking generates peer effects, which raise the consumption levels of problematic drinkers. A shift towards “the culture of alcohol” towards a social norm of teetotalism poses a free-rider problem, so cannot happen unless there is a mass change in individual attitudes, and if the majority do get on the wagon, those that continue to drink would disproportionately be the problematic drinkers, so it does not affect the total social costs that much. To induce society to stop drinking, unless there is a superior outside option generated by the market, we are reliant on the price mechanism and other incentives. If pigouvian taxes priced at the marginal social cost do not induce a teetotal norm, then such a norm is suboptimal. If our concern is crime, simply raise the penalty for booze-fuelled criminality, and increase enforcement of such. If we care about alcoholics getting drunk on the job, then the absolute worst thing we can do is label alcoholism as a disease and make it harder to fire them. Arguably disability law generates a moral hazard issue, increasing rates of alcoholism. Hence government stepping out of our decisions in many cases will actually promote virtue too. By aligning our incentives such that we behave more prosocially, we can achieve better outcomes than reliance on individuals simply opting to act virtuously.

Of course, persuasion that teetotalism is within your own interest can shift your preferences over time. Although I am sceptical of Cowen's argument, his emphasis of the long-run personal harms of alcohol persuaded me to drastically reduce my consumption, and my life is unequivocally better for it. For this, I am grateful. As intellectuals operating in the public domain, I cannot think of a better means to express my gratitude than to engage with an argument seriously, even if I disagree with the overall conclusion. If the argument was bad, I would simply ignore it. Our models, including Becker and Murphy, assume stable preferences. Dynamic preferences are too complicated, so we take an individual's current preferences at the time to be stable at t. Yet we do frequently change our minds, so if our preferences change we just use the same model but with the new preferences treated as stable. Search costs to acquiring new information mean that we do not hold all publicly available information, yet provided that agents act Bayesian upon encountering said new information, this is again consistent with rationality [9]. I see persuasion as another form of information aggregation, and in fact updating your beliefs and preferences is often rational.

In general, I do indeed observe a nonchalance regarding the dangers that alcohol poses. As stigma is correlated with addictiveness, and the prevailing equilibrium for booze is type I addiction, the lack of stigma (except outside religion: most teetotalism in the world tends to be enforced via faith) fosters a shortfall in awareness. We all know that bad things can happen when drunk, yet many of us are oblivious to the long-run ageing effects. Most suffer only a hangover and an embarrassing infringement to ourselves when drunk, rather than a life-changing incident. We are aware of alcoholism, yet we discount that as a “disease” of the minority, rather than a series of rational choices over drinking that drinkers are prone to making. So this relates back to my point on stigma relating to deviance. Precisely because drinking is a social norm, we neglect its harms. Likewise, there is common knowledge of the harms of other substances, so most do not need to be persuaded to abstain from heroin.

A more pertinent flaw in this argument is the slippery-slope. Alcohol generates peer effects analogous to sharing a chocolate cake at a social gathering. Should we all stop eating cake because some people are obese? Taken to its logical conclusion, such reasoning is the justification of totalitarians. We must act not in our selfish interests, but in the interests of society. Yet where do we draw the line? Such reasoning is the exact same justification the CPC uses for its authoritarianism today, and the doctrine of all communist regimes in history. This is also why I am not an effective altruist, as many in that community are prone to this type of thinking, where even harmless acts are shamed as a trivial distraction from saving the world [10].

X. Conclusion

For all these reasons, I am not engaging in the practice of declaring a new year's resolution. Such pledges are neither optimal nor credible. For the sake of our happiness and flourishing, I strongly advise that we all ditch this absurd ritual. As the saying goes, “we only live once”. Live your life, embrace your hedonistic pursuits, and do feel shamed into doing otherwise.

UPDATE (28/12/2025): A reader has brought to my attention the successful temperance movement of India, intertwined deeply with its independence movement. Temperance advocates in America also consistently achieve a substantial level of success throughout all of America’s history. Prohibition is just the tip of the iceberg - there were calls for prohibition and successful shifts towards temperance long before, and there are still hundreds of dry counties today. In my post, I underrated the power of peaceful (and indeed rational) persuasion, and its ability to shift discount rates over time. Attitudes changed with regards to smoking via this tactic; the stigma around marijuana loosened via this tactic.

This is the most convincing flaw in my argument: you can persuade an individual to alter their preferences to live a more virtuous life. Throughout this post I only gave this an afterthought, and mostly treated preferences as fixed. Nonetheless, that persuasion is contingent on rationality, and preferences actually shifting. In environments where there is common knowledge that X activity is not virtuous (vice), yet people indulge anyhow, the probability of persuasion is low, albeit nonzero.

Moreover, it has also occured to me that the peer effects of alcohol are an endogenous investment in its addiction, D(.). You associate with a new friendship group that parties regularly, you feel bad if you were to decline the events, when you go to such events you want to drink to fit in, and so on. Such matching is indeed a large driver of increasing marginal returns, and such social networks are costly to escape (often it entails loneliness). Regardless, this is clearly a rational choice on the part of the individual, yet it does pose the obvious question of how to incentivise sober matches? Developing a superior outside option and focal point is the most effective means that teetotalers will spread its adoption in my view.

As I write, I stumbled across this claim which my prior suggests is representative of the majority of addicts. Your stereotypical homeless junkie is the most extreme case!

It can also be a service such as gambling or escorts. In the rest of this post, I will refer to drug addiction just to reduce the number of words I use.

Arguably, the fact we have to flip a key assumption could suggest some form of illness, if we define illness as any physical or mental abnormality. Not so fast! Recall that increasing returns is a core feature of endogenous growth theory. Beyond introductory classes, we can play with many different modelling assumptions!

Here, we have assumed a rational agent discounts at a constant rate. In practice, many discount at nonlinear rates (their discount rate increases as we head further into the future), known as hyperbolic discounting. Yet this is consistent with existential risk increasing as t increases, so again can be consistent with rationality.

Now we have a solution to the longstanding debate within (philosophy of) psychology over the definition of a mental illness. A mental illness is characterised by persistently irrational behaviour and expectations or beliefs.

Counterintuitively, I can see the increasing marginal utilities of addiction as a rather solid case for redistribution to addicts. Rather than motivated by sympathy, transfers financing an addict’s habit will do eventually more to increase utility than almost anything else. Of course, the costs and externalities with respect to human capital depreciation (even weed imposes substantial externalities via this mechanism!) will also amount, so the overall returns are dire, at least for those of us with normal discount rates.

At least in Western societies and East Asia; teetotalism seems to be the norm elsewhere. A comfortable majority of the world has not drunk alcohol in the past year (a number set to grow with the rise of Islam in the developing world), and almost a majority has not touched a drop!

Anecdotally, cocaine has been blamed for aggression, yet most users also drink alcohol on cocaine, which metabolises in the liver as the distinct drug cocaethylene. There is little data on the effect of coke use per se however.

In my next post, I will explore how addiction responds to exogenous life shocks, which can be modelled as unanticipated price changes or changes to the parameters. I already anticipate that I will make the argument that the rationality of another person's decisions would be a lot more obvious if you hold the same information as they do. Counterintuitively, empathy then promotes selfishness when agents are rational. More on this later…

Peter Singer’s infamous drowning child experiment invokes utilitarianism to justify precisely these actions. However, societal welfare is the aggregation of individual preferences. The first theorem of welfare economics has proven that without market failure (including externalities), that this aggregation is sufficient to maximise welfare. Thus we should only care about offsetting externalities in inventivising prosocial behaviour, and utilitarianism implies selfishness. Ayn Rand was right in my view, selfishness is moral behaviour. Declining to give to charity is not an externality, so he misunderstands the nature of preference aggregation.

The introduction and end, and in the notes. To skip the math, skip sections II and IV-VI, reading only the italics. If you take the derivation of the results at my word, then you can understand the argument without the math.

Could you summarize the essential gist of your argument in a paragraph or two without using any math?